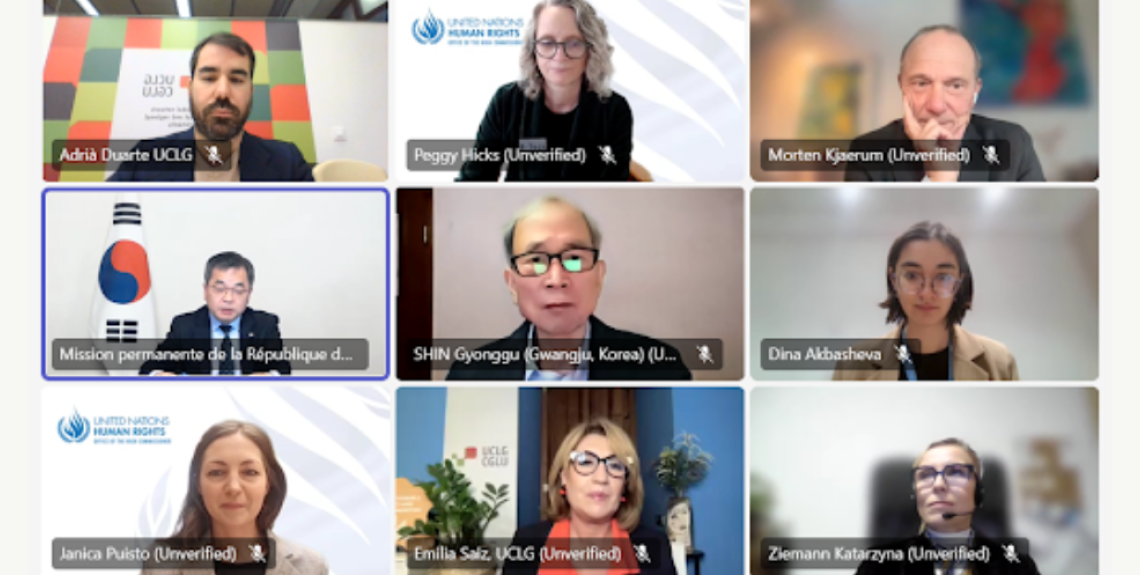

On 26 November, local and regional governments, UN experts, and civil society representatives gathered for the meeting on Local Government and Human Rights, convened by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), in collaboration with United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), the Geneva Human Rights Platform, the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (RWI) and the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Korea in Geneva. The meeting explored how cities and territories around the world are advancing human rights at the local level and highlighted the Guidance Framework for creating a Human Rights City, co-developed by the OHCHR and UCLG.

Local Governments and Human Rights Action

H.E. Mr. Seong Deok Yun, Ambassador and Permanent Representative of the Republic of Korea to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva, opened the session by underscoring the pivotal role of the OHCHR-UCLG Guidance Framework for creating a Human Rights City in empowering local governments to become key actors in human rights localization. He emphasized the importance of locally tailored policies for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the importance of involving local governments in realizing them.

UCLG Secretary-General, Emilia Saiz, emphasized that local and regional governments are on the frontlines of delivering human rights globally, in particular through public service provision, but underlined the need for structured multilateral engagement: “It is important to place human rights at the center of our agenda, but also ensure that there are connections between human rights and other multilateral agendas. Putting public service at the center will change our capacity to deliver human rights.”

Peggy Hicks, OHCHR Director of the Thematic and Special Procedures Division, stressed the urgency of empowering cities and territories amid escalating global challenges, from famine to inequality, and climate change. “Local governments are closer to the populations they serve,” she noted, emphasizing their capacity to innovate and respond effectively to local needs. She also warned that in times of backlash, human rights must be upheld as a shared obligation, not an optional commitment.

Learning from Leading and Emerging Human Rights Cities

Session 1 focused on promising practices and lessons learned in adopting a human rights-based approach to local governance and public service delivery, drawing from the experience of Human Rights Cities and the OHCHR-UCLG Guidance Framework.

Shams Asadi — Human Rights Commissioner of Vienna — reflected on her city’s decade-long journey as a Human Rights City, emphasizing the momentum of the global movement. She emphasized the importance of political commitment, supported by structural tools such as dedicated staff, human rights-based budgeting, and fostering a district-level “culture of human rights.” She stressed the need to reinforce the link between democracy and human rights: “To bring together human rights and democracy, the solution is the human-rights-based approach, with true participation and transparency. At a time when civic space is shrinking, so is trust in institutions.”

Pannarai Chingchitr — Deputy Director-General at the Strategy and Evaluation Department — highlighted Bangkok’s nine-priority roadmap for development, emphasizing that a city is only truly livable when human rights are at the core. The Bangkok Metropolitan Government has formally committed to becoming a Human Rights City, establishing a dedicated committee and training programs to embed human rights in municipal operations. Nonetheless, he underscored that embedding human rights is a long-term journey: “We are in the process of reviewing our operations, to create a proper plan to become a Human Rights City. We need to foster an organizational change to make a city that is truly liveable for all”.

From Gdansk, Katarzyna Ziemann presented the city’s equal treatment model, which prioritizes services for vulnerable groups through initiatives such as an equal treatment center and social campaigns. She highlighted the four core commitments guiding Gdansk’s approach:

-

To pledge the city to be a place where everyone commits to human rights standards

-

To strengthen the protection and fulfillment of all rights, economic, civil, political, and social rights

-

To build a Human Rights City around a new vision of the city, not only around non-discrimination

-

To ensure that Human Rights City is not only a title, but a collective and co-created vision.

Prof. Gyonggu Shin, Executive Director of the Gwangju International Center and Senior Advisor on Human Rights and International Affairs, shed light on the city’s pioneering role, establishing the first human rights charter of Asia, and later institutional structures such as an ombudsman and a Human Rights index for self-assessment.

Morten Kjaerum, Professor and Former Director of the Raoul Wallenberg Institute, emphasized the importance of connecting academic research with local government experience, such as through the RIGHTSCITIES project. He welcomed the emergence of an informal network of partners supporting human rights localization, led by UCLG: “We need to identify what is already there, and see what is missing.”

During the open floor, Adrià Duarte, coordinator of the UCLG Committee on Social Inclusion, Participatory Democracy and Human Rights reiterated UCLG’s commitment to the Human Rights Cities movement, including through the 16 Days of Activism campaign, the renewal of the Charter-Agenda for Human Rights in the City, and the “10, 100, 1.000 Human Rights Cities & Territories by 2030” global campaign. With regard to the Guidance Framework, he emphasized the need to now focus on implementation.

Session 2 featured representatives from New York City, Mexico City, Wallonia-Brussels, and the UN — including Balakrishnan Rajagopal, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing — who showcased innovative practices for strengthening local and regional governments’ engagement with UN human rights mechanisms. Discussions highlighted successful approaches to reporting to and implementing recommendations from the Treaty Bodies, Universal Periodic Review, and Special Procedures.

Looking ahead

Just a decade ago, such a discussion on Human Rights Cities at the UN level would not have been possible. As the movement gains global momentum and cities are increasingly recognized as central actors in human rights protection and provision, participants stressed that the journey is ongoing. Strengthening the movement — through the Global Campaign “10, 100, 1.000 Human Rights Cities & Territories by 2030”, the Charter Agenda for Human Rights in the City, and deployment of the Guidance Framework — is key to transforming commitments into concrete action.

Looking ahead, participants reaffirmed the need for:

-

Renewed political commitment amid growing backlash;

-

Minimum standards and accreditation for Human Rights Cities;

-

Meaningful participation of local and regional governments in UN mechanisms;

-

Strengthening human rights culture and foundations at the local level;

-

A human-rights-based approach to local governance, embedded into all city services and policies;

-

Enhanced international cooperation and exchange of best practices.

The meeting concluded with a shared commitment to advance Human Rights Cities worldwide, ensuring that cities remain at the forefront of protecting, promoting, and localizing human rights.